Spina bifida

| Spina bifida cystica | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

|

|

| ICD-10 | Q05., Q76.0 |

| ICD-9 | 741, 756.17 |

| OMIM | 182940 |

| DiseasesDB | 12306 |

| eMedicine | orthoped/557 |

| MeSH | C10.500.680.800 |

Spina bifida (Latin: "split spine") is a developmental birth defect caused by the incomplete closure of the embryonic neural tube. Some vertebrae overlying the spinal cord are not fully formed and remain unfused and open. If the opening is large enough, this allows a portion of the spinal cord to protrude through the opening in the bones. There may or may not be a fluid-filled sac surrounding the spinal cord. Other neural tube defects include anencephaly, a condition in which the portion of the neural tube which will become the cerebrum does not close, and encephalocele, which results when other parts of the brain remain unfused.

Spina bifida malformations fall into four categories: spina bifida occulta, spina bifida cystica (myelomeningocele), meningocele and lipomeningocele. The most common location of the malformations is the lumbar and sacral areas . Myelomeningocele is the most significant form and it is this that leads to disability in most affected individuals. The terms spina bifida and myelomeningocele are usually used interchangeably.

Spina bifida can be surgically closed after birth, but this does not restore normal function to the affected part of the spinal cord. Intrauterine surgery for spina bifida has also been performed and the safety and efficacy of this procedure is currently being investigated. The incidence of spina bifida can be decreased by up to 75% when daily folic acid supplements are taken prior to conception.

Contents |

Classification

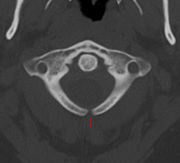

Spina bifida occulta

Occulta is Latin for "hidden." This is one of the mildest forms of spina bifida.[1]

In occulta, the outer part of some of the vertebrae are not completely closed.[2] The split in the vertebrae is so small that the spinal cord does not protrude. The skin at the site of the lesion may be normal, or it may have some hair growing from it; there may be a dimple in the skin, a lipoma, a dermal sinus or a birthmark.[3]

Many people with the mildest form of this type of spina bifida do not even know they have it, as the condition is asymptomatic in most cases.[3] A systematic review of radiographic research studies found no relationship between spina bifida occulta and back pain.[4] More recent studies not included in the review support the negative findings.[5][6][7]

However, other studies suggest spina bifida occulta is not always harmless. One study found that among patients with back pain, severity is worse if spina bifida occulta is present.[8][9]

Spina bifida cystica

In spina bifida cystica, a cyst protrudes through the defect in the vertebral arch. These conditions can be diagnosed in utero on the basis of elevated levels of alpha-fetoprotein, after amniocentesis, and by ultrasound imaging. Spina bifida cystica may result in hydrocephalus and neurological deficits.

Meningocele

The least common form of spina bifida is a posterior meningocele (or meningeal cyst).

In a posterior meningocele, the vertebrae develop normally, however the meninges are forced into the gaps between the vertebrae. As the nervous system remains undamaged, individuals with meningocele are unlikely to suffer long-term health problems, although there are reports of tethered cord. Causes of meningocele include teratoma and other tumors of the sacrococcyx and of the presacral space, and Currarino syndrome, Bony defect with outpouching of meninges.[10]

Myelomeningocele

In this, the most serious and common[11] form, the unfused portion of the spinal column allows the spinal cord to protrude through an opening. The meningeal membranes that cover the spinal cord form a sac enclosing the spinal elements. Spina bifida with myeloschisis is the most severe form of spina bifida cystica. In this defect, the involved area is represented by a flattened, plate-like mass of nervous tissue with no overlying membrane. The exposure of these nerves and tissues make the baby more prone to life-threatening infections.[12]

The protruded portion of the spinal cord and the nerves which originate at that level of the cord are damaged or not properly developed. As a result, there is usually some degree of paralysis and loss of sensation below the level of the spinal cord defect. Thus, the higher the level of the defect the more severe the associated nerve dysfunction and resultant paralysis. People may have ambulatory problems, loss of sensation, deformities of the hips, knees or feet and loss of muscle tone. Depending on the location of the lesion, intense pain may occur originating in the lower back, and continuing down the leg to the back of the knee.

Many individuals with spina bifida will have an associated abnormality of the cerebellum, called the Arnold Chiari II malformation. In affected individuals the back portion of the brain is displaced from the back of the skull down into the upper neck. In approximately 90 percent of the people with myelomeningocele, hydrocephalus will also occur because the displaced cerebellum interferes with the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid.

The myelomeningocele (or perhaps the scarring due to surgery) tethers the spinal cord. In some individuals this causes significant traction on the spinal cord and can lead to a worsening of the paralysis, scoliosis, back pain, or worsening bowel and/or bladder function.

Signs and symptoms

Children with spina bifida often have hydrocephalus, which consists of excessive accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles of the brain.[13]

According to the Spina Bifida Association of America (SBAA), over 73 percent of people with spina bifida develop an allergy to latex, ranging from mild to life-threatening. The common use of latex in medical facilities makes this a particularly serious concern. The most common approach to avoid developing an allergy is to avoid contact with latex-containing products such as examination gloves, condoms, catheters, and many of the products used by dentists.[2]

Pathophysiology

Spina bifida is caused by the failure of the neural tube to close during the first month of embryonic development (often before the mother knows she is pregnant).

Normally the closure of the neural tube occurs around 28 days after fertilization.[14] However, if something interferes and the tube fails to close properly, a neural tube defect will occur. Medications such as some anticonvulsants, diabetes, having a relative with spina bifida, obesity, and an increased body temperature from fever or external sources such as hot tubs and electric blankets can increase the chances a woman will conceive a baby with a spina bifida. However, most women who give birth to babies with spina bifida have none of these risk factors, and so in spite of much research, it is still unknown what causes the majority of cases.

The varying prevalence of spina bifida in different human populations and extensive evidence from mouse strains with spina bifida suggests a genetic basis for the condition. As with other human diseases such as cancer, hypertension and atherosclerosis (coronary artery disease), spina bifida likely results from the interaction of multiple genes and environmental factors.

Research has shown that lack of folic acid (folate) is a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of neural tube defects, including spina bifida. Supplementation of the mother's diet with folate can reduce the incidence of neural tube defects by about 70 percent, and can also decrease the severity of these defects when they occur.[15][16][17] It is unknown how or why folic acid has this effect.

Spina bifida does not follow direct patterns of heredity like muscular dystrophy or haemophilia. Studies show that a woman who has had one child with a neural tube defect such as spina bifida, have about a three percent risk of having another child with a neural tube defect. This risk can be reduced to about one percent if the woman takes high doses (4 mg/day) of folic acid before and during pregnancy. For the general population, low-dose folic acid supplements are advised (0.4 mg/day).

Prevention

There is no single cause of spina bifida nor any known way to prevent it entirely. However, dietary supplementation with folic acid has been shown to be helpful in preventing spina bifida (see above). Sources of folic acid include whole grains, fortified breakfast cereals, dried beans, leaf vegetables and fruits.[18]

Folate fortification of enriched grain products has been mandatory in the United States since 1998. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Public Health Agency of Canada[19] and UK recommended amount of folic acid for women of childbearing age and women planning to become pregnant is at least 0.4 mg/day of folic acid from at least three months before conception, and continued for the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.[20] Women who have already had a baby with spina bifida or other type of neural tube defect, or are taking anticonvulsant medication should take a higher dose of 4–5 mg/day.[20]

Certain mutations in the gene VANGL1 are implicated as a risk factor for spina bifida: these mutations have been linked with spina bifida in some families with a history of spina bifida.[21]

Pregnancy screening

Neural tube defects can usually be detected during pregnancy by testing the mother's blood (AFP screening) or a detailed fetal ultrasound. Spina bifida may be associated with other malformations as in dysmorphic syndromes, often resulting in spontaneous miscarriage. However, in the majority of cases spina bifida is an isolated malformation.

Genetic counseling and further genetic testing, such as amniocentesis, may be offered during the pregnancy as some neural tube defects are associated with genetic disorders such as trisomy 18. Ultrasound screening for spina bifida is partly responsible for the decline in new cases, because many pregnancies are terminated out of fear that a newborn might have a poor future quality of life. With modern medical care, the quality of life of patients has greatly improved.[14]

Treatment

There is no known cure for nerve damage due to spina bifida. To prevent further damage of the nervous tissue and to prevent infection, pediatric neurosurgeons operate to close the opening on the back. During the operation for spina bifida cystica, the spinal cord and its nerve roots are put back inside the spine and covered with meninges. In addition, a shunt may be surgically installed to provide a continuous drain for the cerebrospinal fluid produced in the brain, as happens with hydrocephalus. Shunts most commonly drain into the abdomen. However, if spina bifida is detected during pregnancy, then open fetal surgery can be performed.

Most individuals with myelomeningocele will need periodic evaluations by specialists including orthopedists to check on their bones and muscles, neurosurgeons to evaluate the brain and spinal cord and urologists for the kidneys and bladder. Such care is best begun immediately after birth. Most affected individuals will require braces, crutches, walkers or wheelchairs to maximize their mobility. As a general rule, the higher the level of the spina bifida defect the more severe the paralysis, but paralysis does not always occur. Thus, those with low levels may need only short leg braces while those with higher levels do best with a wheelchair, and some may be able to walk unaided. Many will need to manage their urinary system with a program of catheterization. Most will also require some sort of bowel management program, though some may be virtually unaffected.

Fetal surgery clinical trials

Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS)[22] is a phase III clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of fetal surgery to close a myelomeningocele. This involves surgically opening the pregnant mother's abdomen and uterus to operate on the fetus. This route of access to the fetus is called "open fetal surgery". Fetal skin grafts are used to cover the exposed spinal cord, to protect it from further damage caused by prolonged exposure to amniotic fluid. The fetal surgery may decrease some of the damaging effects of the spina bifida, but at some risk to both the fetus and the pregnant woman.

In contrast to the open fetal operative approach tested in the MOMS, a minimally invasive approach has been developed by the German Center for Fetal Surgery & Minimally Invasive Therapy at the University of Bonn, Germany.[23] This minimally invasive approach uses three small tubes (trocars) with an external diameter of 5 mm that are directly placed via small needle punctures through the maternal abdominal wall into the uterine cavity. Via this route, the unborn can be postured and its spina bifida defect be closed using small instruments. In contrast to open fetal surgery for spina bifida, the fetoscopic approach results in less trauma to the mother as large incisions of her abdomen and uterus is not required.

Epidemiology

Spina bifida is one of the most common birth defects, with an average worldwide incidence of 1–2 cases per 1000 births, but certain populations have a significantly greater risk.

In the United States, the average incidence is 0.7 per 1000 live births. The incidence is higher on the East Coast than on the West Coast, and higher in whites (1 case per 1000 live births) than in blacks (0.1–0.4 case per 1000 live births). Immigrants from Ireland have a higher incidence of spina bifida than do nonimmigrants.[24][25]

The highest incidence rates worldwide were found in Ireland and Wales, where 3–4 cases of myelomeningocele per 1000 population have been reported during the 1970s, along with more than six cases of anencephaly (both live births and stillbirths) per 1000 population. The reported overall incidence of myelomeningocele in the British Isles was 2–3.5 cases per 1000 births.[24][25] Since then, the rate has fallen dramatically with 0.15 per 1000 live births reported in 1998[14], though this decline is partially accounted for by the fact that some foetuses are aborted when tests show signs of spina bifida (see Pregnancy screening below).

Parents of children with spina bifida have an increased risk of having a second child with a neural tube defect.[24][25]

This condition is more likely to appear in females; the cause for this is unknown.

Society and culture

Media

Nadia DeFranco, a young girl living with spina bifida was the subject of a Canadian short documentary I'll Find a Way, winner of the Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film in 1977.[26]

Notable people

People of note born with spina bifida:

- Jade Calegory, actor, best known for his role as the disabled main character in Mac and Me.

- Lucy Coleman, from the children's TV show Signing Time!

- James Connelly, US Paralympian, 2006 Bronze Medal Winner; Sledge hockey

- Jean Driscoll, Paralympian and eight-time Boston Marathon winner

- Guro Fjellanger, Norwegian politician

- Aaron Fotheringham, American extreme wheelchair athlete

- Dame Tanni Grey-Thompson, British Paralympian

- Lawrence Gwozdz, US saxophonist

- Blaine Harrison,[27] of the British band Mystery Jets

- Robert Hensel, Guinness record holder

- Rene Kirby,[28] US actor in films such as Shallow Hal and Stuck on You

- Matt Lloyd, British Paralympian

- John Mellencamp,[29] US rock and roll musician

- Dr. Karin Muraszko,[30] chair of Department of Neurosurgery at University of Michigan, first female appointed to position in the country

- David Proud, British actor

- Jesse Richards, American artist and filmmaker, founder of Remodernist film

- George Schappell, conjoined twin and country music musician

- Bobby Steele, US punk rock guitarist and songwriter

- Jeffrey Tate, British conductor

- Dale Tryon, Baroness Tryon, Australian socialite and friend of Prince Charles

- Hank Williams, US country music singer

- Lucinda Williams,[31] US country music singer/songwriter

- Miller Williams,[31] US poet

- Justin Yoder, US soap box racer

- Adam Hall, New Zealand Paralympian, 2010 Gold Medal Winner

- Chandre Oram, an Indian man famous for his tail

- Jack Kramme, Australian peace activist.

- Blaine Harrison, lead singer of the English band Mystery Jets

- Dr Jack Pryor, Professor of Developmental Neurology, University of Warwick

- Quinn James McLaughlin (Adventurer, Author, Handicap Mountain Bicycle Designer)

- Samuel Armas (an early recipient of open fetal surgery)

See also

- Valproic acid

- Pseudomeningocele

- Malone antegrade continence enema (MACE)

- Meningohydroencephalocoele

- Mitrofanoff appendicovesicostomy

References

- ↑ "What Is Spina Bifida?". ASBAH. http://www.asbah.org/Spina+Bifida/informationsheets/whatisspinabifida.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Foster, Mark R. "Spina Bifida". http://www.emedicine.com/orthoped/TOPIC557.HTM. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Spina Bifida Occulta". ASBAH. http://www.asbah.org/Spina+Bifida/informationsheets/spinabifidaocculta.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ↑ van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM (1997). "Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of observational studies". Spine 22 (4): 427–34. doi:10.1097/00007632-199702150-00015. PMID 9055372.

- ↑ Iwamoto J, Abe H, Tsukimura Y, Wakano K (2005). "Relationship between radiographic abnormalities of lumbar spine and incidence of low back pain in high school rugby players: a prospective study". Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 15 (3): 163–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2004.00414.x. PMID 15885037.

- ↑ Iwamoto J, Abe H, Tsukimura Y, Wakano K (2004). "Relationship between radiographic abnormalities of lumbar spine and incidence of low back pain in high school and college football players: a prospective study". The American journal of sports medicine 32 (3): 781–6. doi:10.1177/0363546503261721. PMID 15090397.

- ↑ Steinberg EL, Luger E, Arbel R, Menachem A, Dekel S (2003). "A comparative roentgenographic analysis of the lumbar spine in male army recruits with and without lower back pain". Clinical radiology 58 (12): 985–9. doi:10.1016/S0009-9260(03)00296-4. PMID 14654032.

- ↑ Taskaynatan MA, Izci Y, Ozgul A, Hazneci B, Dursun H, Kalyon TA (2005). "Clinical significance of congenital lumbosacral malformations in young male population with prolonged low back pain". Spine 30 (8): E210–3. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000158950.84470.2a. PMID 15834319.

- ↑ Avrahami E, Frishman E, Fridman Z, Azor M (1994). "Spina bifida occulta of S1 is not an innocent finding". Spine 19 (1): 12–5. doi:10.1097/00007632-199401000-00003 (inactive 2010-03-19). PMID 8153797.

- ↑ Kaplan hand book

- ↑ "Myelomeningocele". NIH. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001558.htm. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic

- ↑ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 T. Lissauer, G. Clayden. Illustrated Textbook of Paediatrics (Second Edition). Mosby, 2003. ISBN 0-7234-3178-7

- ↑ Holmes LB (1988). "Does taking vitamins at the time of conception prevent neural tube defects?". JAMA 260 (21): 3181. doi:10.1001/jama.260.21.3181. PMID 3184398.

- ↑ Milunsky A, Jick H, Jick SS, et al. (1989). "Multivitamin/folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy reduces the prevalence of neural tube defects". JAMA 262 (20): 2847–52. doi:10.1001/jama.262.20.2847. PMID 2478730.

- ↑ Mulinare J, Cordero JF, Erickson JD, Berry RJ (1988). "Periconceptional use of multivitamins and the occurrence of neural tube defects". JAMA 260 (21): 3141–5. doi:10.1001/jama.260.21.3141. PMID 3184392.

- ↑ "Folic Acid Fortification". FDA. February 1996. http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/wh-folic.html.

- ↑ "Folic Acid - Public Health Agency of Canada". http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/fa-af/index.html.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Why do I need folic acid?". NHS Direct. 2006-04-27. http://www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/articles/article.aspx?articleId=913. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ Kibar Z, Torban E, McDearmid JR, Reynolds A, Berghout J, Mathieu M, Kirillova I, De Marco P, Merello E, Hayes JM, Wallingford JB, Drapeau P, Capra V, Gros P (2007). "Mutations in VANGL1 associated with neural-tube defects" (–Scholar search). N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (14): 1432–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060651. PMID 17409324. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=17409324&promo=ONFLNS19.

- ↑ MOMS website and MOMS summary on ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ http://www.ukb.uni-bonn.de/42256BC8002AF3E7/vwWebPagesByID/BE136B90886FDF44C1256E3D0053C26A

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Lemire RJ (1988). "Neural tube defects". JAMA 259 (4): 558–62. PMID 3275817.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Cotton P (1993). "Finding neural tube 'zippers' may let geneticists tailor prevention of defects". JAMA 270 (14): 1663–4. PMID 8411482.

- ↑ Shaffer, Beverly (1977). "I'll Find a Way". National Film Board of Canada Web site. http://www.nfb.ca/film/Ill_find_a_way. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ Martin, Dan (2008-06-14). "Dan Martin meets Blaine from the Mystery Jets". guardian.co.uk. http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/jun/14/features16.theguide. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ Interview with actress Sascha Knopf from Shallow Hal

- ↑ John Mellencamp bio from Yahoo Music

- ↑ Gavin, Kara (2001). "U-M Neurosurgeon Urges Women to Protect their Children by Taking Folic Acid". Medicine at Michigan 3 (2). http://www.medicineatmichigan.org/magazine/2001/spring/huron/huron12.asp. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Lewine, Edward (March 1, 2009). "Domains: Country House". New York Times (The New York Times Company): pp. MM17. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/01/magazine/01wwln-domains-t.html. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

External links

- CDC: Spina Bifida

- The International Federation for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus - Umbrella organization

- Association for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus

- National Spina Bifida Association

- Spina Bifida Support Forum

- UCSF Fetal Treatment Center: Myelomeningocele (Spina Bifida)

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke: Spina Bifida Information Page

- Mayo Clinic: Spina bifida Symptoms

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||